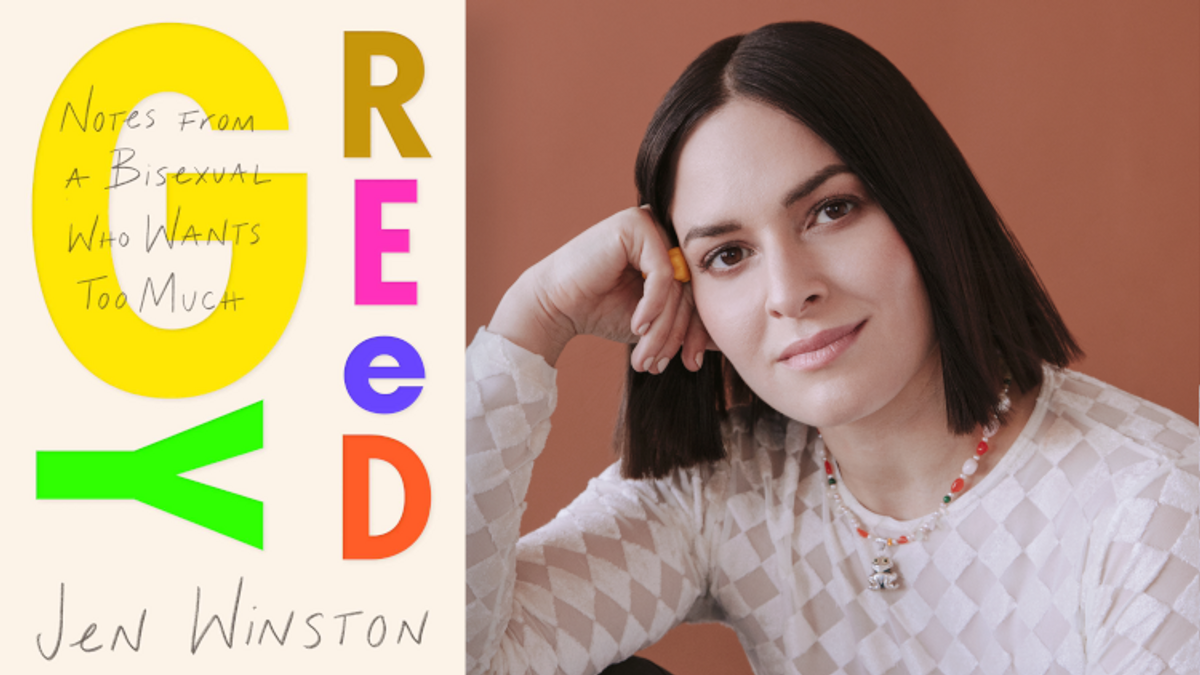

"Bisexuality isn't just an identity," Jen Winston writes in their new memoir, Greedy: Notes from a Bisexual Who Wants Too Much. "It's a lens through which to reimagine the world."

Winston came to embrace their sexuality after a long, often arduous process of recognizing and ultimately learning to discard the binary way in which desire is presented in society. Monosexuality (being attracted to only one gender) is still considered the norm, even amongst those within the LGBTQ+ community. While queer people have made leaps and bounds in terms of progress recently, we've done a remarkably bad job at demystifying and breaking down the confusion that still colors so much of how bisexuality is viewed.

When Winston began to get comfortable with and name their bisexuality, they applied this new binary-free lens to every part of their life, finding it also gave them language for describing their experience of gender. The misconception that bisexuality is an endorsement of the gender binary is one reason why they were originally hesitant to claim the label, bi, for themself. "I didn't want to say the word out loud because I was like, 'I don't endorse the gender binary, personally.' So I was like, 'I can't identify as this,'" they said. "It wasn't until I did a bunch of research on the history of the movement that I realized it's always been really gender-expansive and gender-inclusive."

Pulling from their own experiences and a wealth of research, their new book, Greedy, details the winding road that lead them to embrace both their bisexuality and nonbinary identities.

To celebrate the release of their book, Jen Winston talks with the LGBTQ&A podcast about the confusion the public still has around bisexuality, why saying things like "Everyone is bi" invalidates bisexuality, and why they still feel a tinge of imposter syndrome when it comes to their gender.

You can read an excerpt below and listen to the full interview on Apple Podcasts.

Masters: I was surprised to read in your book that bisexuals have a higher rate of sexual assault and substance abuse. Did your research turn up any reasons for why that is?

Winston: Not overtly. That's the short answer. I couldn't really find anything that talked about the causation of it.

It's a variety of things, not just one thing. But with these stats about bisexuality, they were so shocking to me because I couldn't figure out why. I was like, "What? Bisexuality doesn't seem like a big enough deal to cause this outcome." But then I realized, "Oh, that's my internalized biphobia and of course it's a big enough deal." Of course, it's actually causing people to have mental health challenges and anxiety.

It just really blew my mind because I don't think I ever saw my bisexuality as valid enough to warrant those types of results. Then when I looked at my lived experience I was like, "Oh, yeah." I put myself in all these vulnerable sexual scenarios because I was trying to figure out what was going on. I drank a lot because I felt anxious and I'm not very much an anxious person, but in most sexual scenarios I felt anxious, especially anything that was queer adjacent.

JM: We can flippantly say that "everyone's bi" or "no one cares," but to your point, there are actual, real-world costs.

JW: Yeah. "Everyone is bisexual" is my favorite thing to point out is actually a microaggression against bi people because it implies that if everyone's bisexual, no one is bisexual and it's not worth talking about and it doesn't matter.

It's so often dismissed as something that we don't need to talk about, which is why I wanted to tell my story, but also look at bisexuality as a political lens because as an idea, it can be really helpful for all of us to grasp.

JM: You wrote, "Bisexuality is not just an identity, it's a lens through which to reimagine the world." Can you explain more about that?

JW: I really came into and embraced my bisexuality in parallel with unlearning about binary systems, in general. Essentially, when I was unlearning my binary thinking outside of my sexuality, it helped me understand my bisexuality. Then when I understood my bisexuality, I was able to look at the world through a less binary lens.

I especially applied that to my gender and I'm getting more comfortable saying this out loud, but I identify as nonbinary and it's still weird--

JM: Why is it weird?

JW: It's weird because I have imposter syndrome around it, but my bisexuality is what really gave me the tools to be like, "You can identify however you want. It's yours to own and it's just for you." I try not to take up a lot of space as a nonbinary person online, but it's definitely something that I'm continuing to figure out.

JM: It took a lot of time to figure out your bisexuality, as you write. It sounds like you're in the same process with your gender.

JW: Yes. I think I'm more comfortable with naming the process of being in the questioning phase because of bisexuality.

I think another misconception about bisexuality is that it endorses the gender binary and that was another reason I didn't want to say the word out loud because I was like, "I don't endorse the gender binary, personally." So I was like, "I can't identify as this." But, the word "pansexual" didn't really hit me the right way and the word queer didn't feel strong enough, I guess. I was like, "I don't deserve that."

So, "bisexual" still felt right for me and it wasn't until I did a bunch of research on the history of the movement that I realized it's always been really gender-expansive and gender-inclusive.

JM: Do you find that in queer spaces, you make it a point to broadcast your queerness so that people don't assume that you're straight?

JW: Yeah, absolutely. I have literally been doing that forever. I think for a while I went with the idea that that's bi privilege. That's a big thing that non-bisexual people say about the bi community, that we are seeking straight privilege. But ultimately, you can have heterosexual presenting privilege when you're in a relationship that presents as straight, but you're still closeted and invisibility takes a different toll on you.

Often coming out can just make you feel more like yourself, you know? That's what it's about. But people don't feel like they should come out unless they want to act on it, and so a lot of bi people in relationships stay closeted.

JM: To that "invisibility" of bi-ness, do you find that you're constantly having to out yourself?

JW: Oh, yeah. That's why I wrote this book. It's weird. The book is very affirming to me to see it. I'm like, "Yep. You're bisexual, Jen."

But honestly, I came here today with cuff jeans, which is a stereotype of bi culture and sometimes I have a fake nose ring. I lost it recently. But when I put it in, I feel bisexual. All queer people do this, but there are things like that that I have deemed bisexual in my mind and I'm like, "I'm doing a bisexual behavior."

But yeah, all I talk about on the internet is being bisexual. But I do really love it because a lot of people are surprised I could write a whole book about it because they didn't realize that bisexuality has all these different effects on people. But also, that it's such a political identity and that it challenges binaries in so many ways.

JM: Early on in the book, before you'd really got to know your bisexuality, you wrote that you felt like if you kept dating men, then no one would believe that you're actually queer, least of all yourself.

JW: It's almost challenging to discern queer attraction, not for the lack of attraction to what society tells you to be attracted to. That sentence that you just read is actually even after I'd come out. A guy was asking me to go on a date, but I'd just come out as bi and I was like, "Oh God, do I do this? I just came out. I don't want to keep dating men."

JM: Oh, so growing up, my identity as a gay man was reinforced by my lack of sexual attraction to women. You're saying you didn't have any sort of reinforcement because you were attracted to all genders.

JW: Yeah. It seemed like a mess that I wanted to avoid. My parents one time, I remember them saying, "If you were a lesbian, that would be okay." Which is a very sweet, amazing thing for my parents to say. But I was like, "I'm not." I wasn't, so I was like, "No, I'm not." I never opened the conversation again, until I came out later. Even though they gave me like an inch to come out as a lesbian, it wasn't the same as giving me space to come out as bi.

JM: Or even non-binary.

JW: Or even non-binary. I don't know that they fully understand that part yet, but they're trying. I'm proud of my parents for working on their pronouns for my partner because my partner exclusively uses they/them pronouns.

For me, if they/them pronouns don't come naturally to someone, it means that they probably still have a binary way of thinking about the world, which is fine. That's how I read it now because my bisexuality really helped me kind of understand this space in-between, then I was able to apply that to gender. So now, I really view my bisexuality as such a gift.

JM: We were talking about you doubting your bisexuality. When did that go away?

JW: I think part of it was that I never was able to have a good sexual experience with a queer person because I had so much self-doubt and imposter syndrome in those spaces. After I came out, I was like, "Enough is enough. Start having some bad sex so you can get to some good sex, eventually."

I think I was feeling very affirmed in my sexuality right when I met my current partner. So, I wouldn't credit them entirely, although they would be like, "It's me, it's me, it's me who did it." But, I was feeling very secure in myself by that point and I think that's why we hit it off.

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Greedy by Jen Winston is available now.

Recent podcast guests who also discussed their bisexuality include Ashley C. Ford, Charles M. Blow, Carolina de Robertis, Melissa Febos, and Lili Reinhart.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters.

New episodes come out every Tuesday.