At 10:02 a.m. Eastern on June 26, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court changed America forever.

In handing down its decision in Obergefell v. Hodges -- declaring marriage to be a constitutionally protected right for same-sex couples -- the court immediately made the lives of millions better. That doesn't happen often: Most progress in an obstreperous country like the United States happens incrementally. But with Obergefell, the Supreme Court wiped out dozens of discriminatory measures, scrubbing away decades of antigay prejudice. Suddenly, anti-LGBT states had no excuse to degrade same-sex couples, no legal rationale to deny them marriage licenses. The worldwide push for marriage equality was given an inestimable boost, as marriage equality rights advocates in countries like Australia looked to the Supreme Court for inspiration. And here in America, in an instant, gays and lesbians made an enormous step toward becoming equal citizens under the law.

The ruling was 5-4, with a sharp, bitter split between the majority and the dissenters. But in a sense, every justice played a role in bringing constitutional marriage equality to a reality.

Start with Justice Anthony Kennedy, author of the court's quartet of gay rights opinions. Kennedy grew up in the shadow of the great liberal Chief Justice Earl Warren, a Kennedy family friend during his days as California governor. Kennedy may side more frequently with the court's conservative bloc -- but on issues of constitutional dignity, he swings to the left. In a sense, Kennedy has been writing his way toward Obergefell since 1996, when he held in Romer v. Evans that the Constitution bars legislation based on "animus" against gays. From that point on, constitutional marriage equality was inevitable. Kennedy just had to wait for the country to catch up to the court.

Kennedy's colleagues in the majority may have been silent on decision day, but each contributed to Obergefell in vital ways. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan grilled Michigan's solicitor general at oral arguments, leading him to assert, inanely, that marriage doesn't bestow dignity. Justice Stephen Breyer joined in, demanding to know why Michigan refused to recognize same-sex unions when marriage itself is a constitutionally protected "fundamental right." (The "equal dignity" of gay people and the "fundamental right" of marriage comprised the bulk of Kennedy's opinion.) And Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg set the stage for Obergefell in a 2010 case, writing that, in the context of sexual orientation, "our decisions have declined to distinguish between status and conduct." Being gay, in other words, is more than just having gay sex: It is an identity, one which finds protection under the Constitution.

(RELATED: The Finalists for Person of the Year)

The court's conservatives also contributed to Obergefell's power, albeit inadvertently. The four dissenters were so outraged by Kennedy's decision that they threw a temper tantrum, with each justice penning his own opinion. Their strategy may have been to drown out the majority opinion, weighing it down with objections until it seemed illegitimate. But this ploy backfired. The cacophony of complaints drowned each other out, making all four justices' rambling counterarguments easy to ignore.

Anybody who does take the time to read the Obergefell dissents may be startled by their flimsiness. Chief Justice John Roberts's opinion angrily accuses the majority of returning to the days when the court elevated business interests over democracy. Coming from the justice who has orchestrated the dismantlement of campaign finance restrictions, this charge is hard to take seriously. Roberts also stoops to out-of-character acrimony, scolding any gay couples who dared to celebrate the Constitution following the ruling. (The Constitution "had nothing to do with it," he huffs.) An unusually canny justice, Roberts often plays the long game. But his condescending admonishment to gay and lesbian Americans that the Constitution doesn't protect their fundamental rights is likely to alienate future generations. How can you trust the legal reasoning of a man who brazenly proclaimed that same-sex couples don't deserve equal justice under the law?

Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito's dissents are equally unpersuasive. Thomas argues that the government cannot add or subtract from anyone's dignity, claiming that slaves were not stripped of their dignity when the government allowed them to be enslaved. The problem with this argument is that it doesn't even respond to Kennedy, who wrote that the government must recognize gay people's inherent dignity, not bestow it. Thomas wastes 18 pages responding to an argument that nobody made.

(RELATED: Take Our Poll to Pick Your Person of the Year)

Alito, too, misses the mark, choosing to fuel the Christian persecution complex rather than make a principled legal argument. "Those who cling to [their] old beliefs," Alito frets, will soon only be able "to whisper their thoughts in the recesses of their homes"; if they "repeat those views in public, they will risk being labeled as bigots."

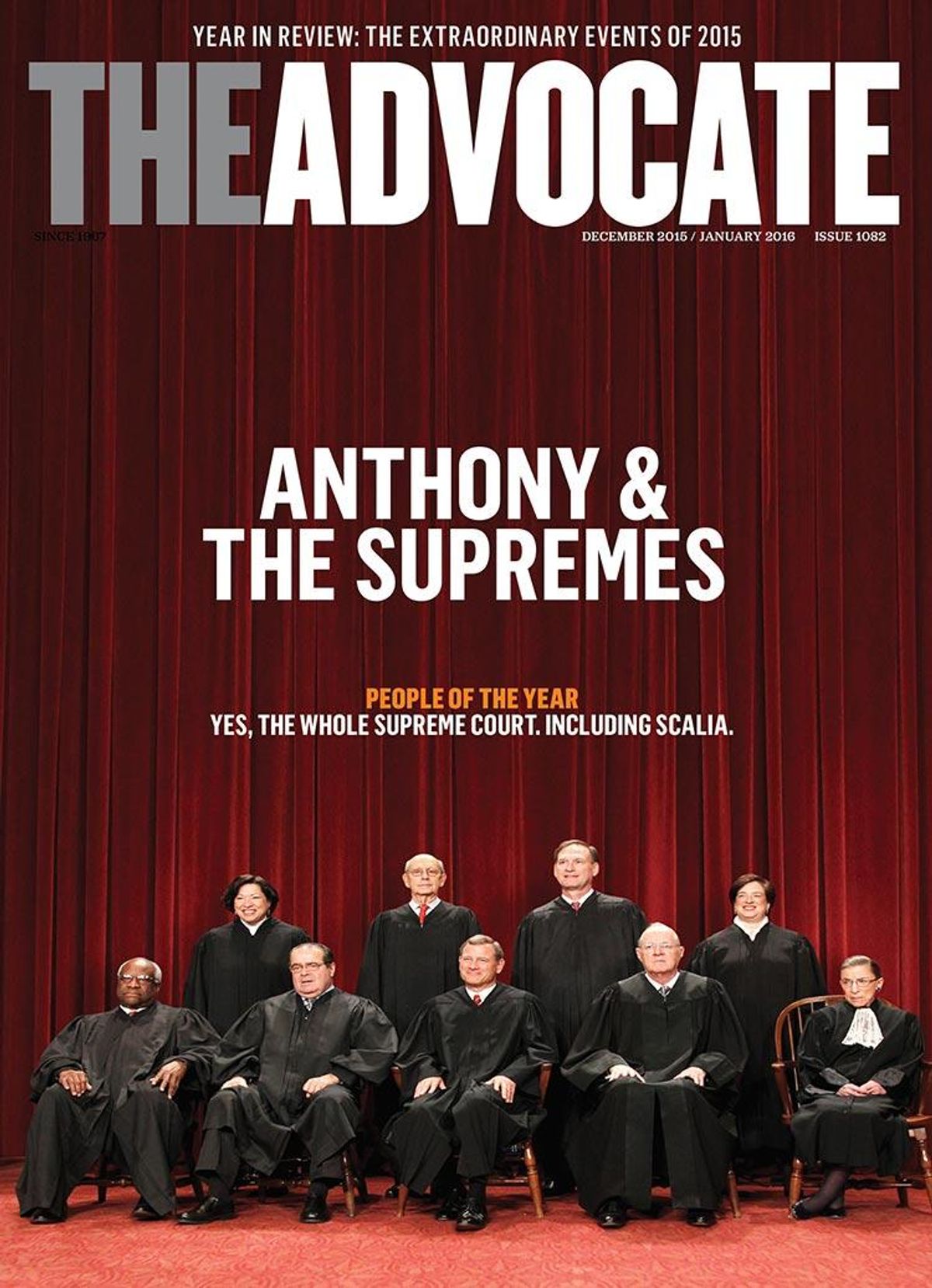

Above, first row, from left: Associate Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Antonin Scalia. Middle row, from left: Associate Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Anthony M. Kennedy, Samuel Anthony Alito. Bottom row, from left: Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Associate Justice Elana Kagan

AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais; AP Photo/Charles DhaRapak (Alito, Kennedy, Sotomayor)

That's right, the government has long barred gay couples from visiting each other in the hospital, adopting their own children, even being buried next to one another -- but it's Christians who are the real victims here. The mere possibility that Christians may be called bigots is, for Alito, a good enough reason to deprive gays of their rights.

Of course, Justice Antonin Scalia has long been an unexpected MVP for marriage equality advocates, and he continued that role in Obergefell. For decades, Scalia has prophesied with dread that each of the court's gay rights decisions would lead to some future catastrophe. In Romer, Scalia suggested the court may soon strike down sodomy bans. When the court proved him right seven years later, Scalia noted that its reasoning "leaves on pretty shaky grounds state laws limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples." Exactly 10 years later, the court invalidated the federal Defense of Marriage Act in United States v. Windsor -- and Scalia threw a hissy fit, actually rewriting the opinion to demonstrate how it would soon be used to strike down state-level marriage bans. Two years later, in Obergefell, the court proved him right.

Those two years were probably the single most important period in the legal struggle for gay equality, as dozens of judges invalidated marriage bans from Alabama to Alaska. Many of these judges didn't just rely on Windsor -- they relied on Scalia's Windsor dissent, writing approvingly that Scalia read Windsor to mandate marriage equality. His dissent propelled the marriage movement to an early finish, persuading a swarm of lower courts to rule, quickly and vehemently, in favor of equality.

(RELATED: A Letter from the Editor on Remembering 2015)

Perhaps recognizing his own role in precipitating Obergefell, Scalia shifted away from prophecies this time around -- and instead aimed his ire at Kennedy himself. Scalia lambastes Kennedy's writing style, criticizing him for employing "the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie." He pillories Kennedy's "inspirational pop-philosophy" as "profoundly incoherent," "pretentious," and "egotistic."

These startlingly personal attacks can only serve to push Kennedy further toward the welcoming embrace of the progressive bloc as new plaintiffs try to expand upon the court's newly broadened vision of constitutional liberty. Kennedy's "equal dignity" rationale has already been invoked in a challenge to Mississippi's antigay adoption ban, and to thwart county clerk Kim Davis's attempt to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples. It will remain a crucial tool as advocates strive to extend the ruling -- and combat efforts to undermine it. Obergefell's immediate impact -- securing, beyond a doubt, LGBT Americans' constitutional right to marry -- was massive enough. Its reverberations may turn out to be just as momentous.

In the days following Obergefell, Kennedy was lionized as a gay rights luminary. He is -- but it was really the court itself that was the hero of the moment. Without its independence, its position as the ultimate arbiter of the law, gays and lesbians in America would still be denied access to the fundamental institution of marriage. Supreme Court decision-making involves a certain kind of sorcery which transforms an individual voice into binding legal precedent. The power of that voice lends each ruling legitimacy, and the prestige of the institution makes each ruling enforceable. It may have been Kennedy who wrote that the Constitution grants gay couples "equal dignity in the eyes of the law." But it is the Supreme Court of the United States that made that judgment a constitutional command.