As a youth growing up in Chicago, Phill Wilson had a Cuban fetish. The Spanish literature major romanticized the island nation, which was off-limits to U.S. travelers since 1961.

A half-century later, Wilson -- now the out president of the Los Angeles-based Black AIDS Institute --would find himself en route to Havana, not just to soak up Cuban culture, but to see what the U.S. and Cuba could learn from each other in the fight against HIV and homophobia.

Wilson led a delegation of 15 gay men, many of color, to Cuba for two weeks starting on Christmas Eve; that was less than a year after President Obama helped normalize the once-strained relationship between the U.S. and communist Cuba.

After news broke last year of the lifting of the trade embargo and easing of the travel ban, "my interest in Cuba was reignited," Wilson says. "Then I began to study the African influence in Cuba, and I've been familiar for a while with what they're doing around HIV and AIDS. Given that, I thought it would be great to sponsor a gay men of color HIV delegation to Cuba."

Wilson says his team was greeted warmly, meeting with government officials, everyday Cubans, and people living with HIV. Wilson was impressed with the nation's response to the disease, which has been greatly aided by the public information campaign of Mariela Castro, the LGBT-supportive daughter of Cuban president Raul Castro.

"From a public health perspective, from a human rights perspective, they are light years ahead of where we are with HIV," Wilson says. "The evidence of that is even in a resource-poor setting, where they still have shortages, the epidemic is much more contained than the epidemic in the U.S. And for people living with HIV there are much fewer barriers to accessing care."

Cubans have universal health care and don't worry about losing coverage and paying ridiculously high premiums or co-pays, Wilson says. Housing struggles, which are common to Americans living with HIV, are mostly nonexistent in Cuba.

HIV-positive Cubans live with stigma like their American counterparts, but Wilson says it felt different there.

"Very early on, [officials] determined that this is a disease -- a medical disease -- and it should be treated as such," Wilson says.

Cuba is lagging in knowledge of pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a daily regimen that's shown to reduce HIV transmission by up to 92 percent. Treatment as prevention remains a foreign concept, but he believes that will change, irregardless of American influence.

"It's a logical step in HIV prevention and much of what's driving the Cuban response to HIV is the logical thing to do if one wants to stop a disease," Wilson says.

The "robust" gay and trans scene -- which is how Wilson and others describe queer life in Cuba -- also takes ownership in keeping themselves healthy. All the gay bars and clubs that Wilson visited carried information and resources on HIV -- and there were no shortage of venues tailored to gay and bi men. Wilson was pleasantly surprised at how open queer life was.

"The fact that there are gay clubs and people seem to be living their lives pretty openly and freely seems to be very clear to me," he says. "It's not like there are gay men who are hiding and fearful of being entrapped and imprisoned, like the movie Before Night Falls. That Cuba doesn't exist anymore."

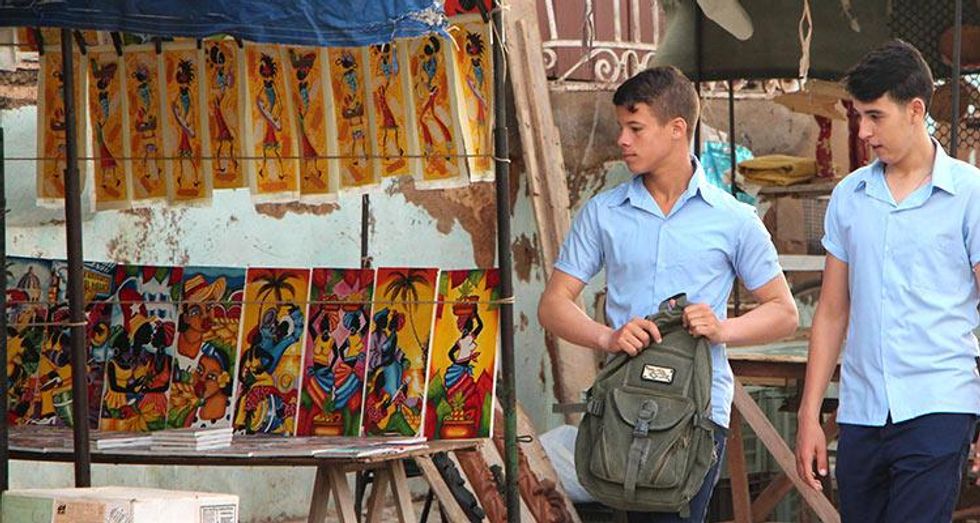

Wilson says life in Havana is not like life in L.A. or New York, though. Internet service is spotty and many buildings are in disrepair. Thankfully, UNESCO is helping to save some of Havana's crumbling architecture, even amidst a current building boom in the nation. Wilson says while there is poverty, there's also signs of wealth -- his team rented a four-story Cuban mansion via Airbnb -- and a sense of entrepreneurship pervades the country. "There are two Cubas," is how he describes it.

With Americans streaming in, Wilson encourages Americans to visit "before [Cuba] turns into South Beach."

"If we go as gay Americans, we should go with a high level of respect," he says. "The Cubans are excited to welcome Americans but they're also very proud and patriotic. Go with a goal of learning and being respectful and trying to get a better grasp of what it's been like being a Cuban for the past 50 or 60 years."

[RELATED: Cuba: The New Gay Paradise?]

[RELATED: Eyes on Cuba]