News

Fired After Joining a Gay Softball Team, This Man Is Fighting Back

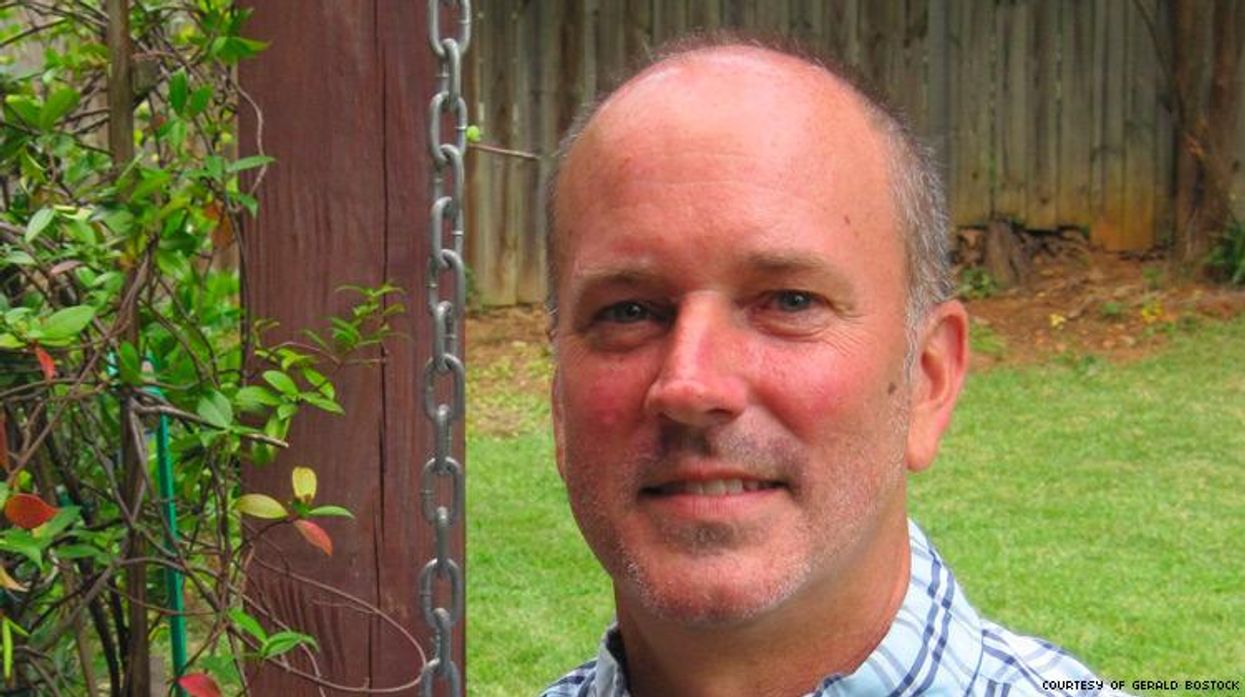

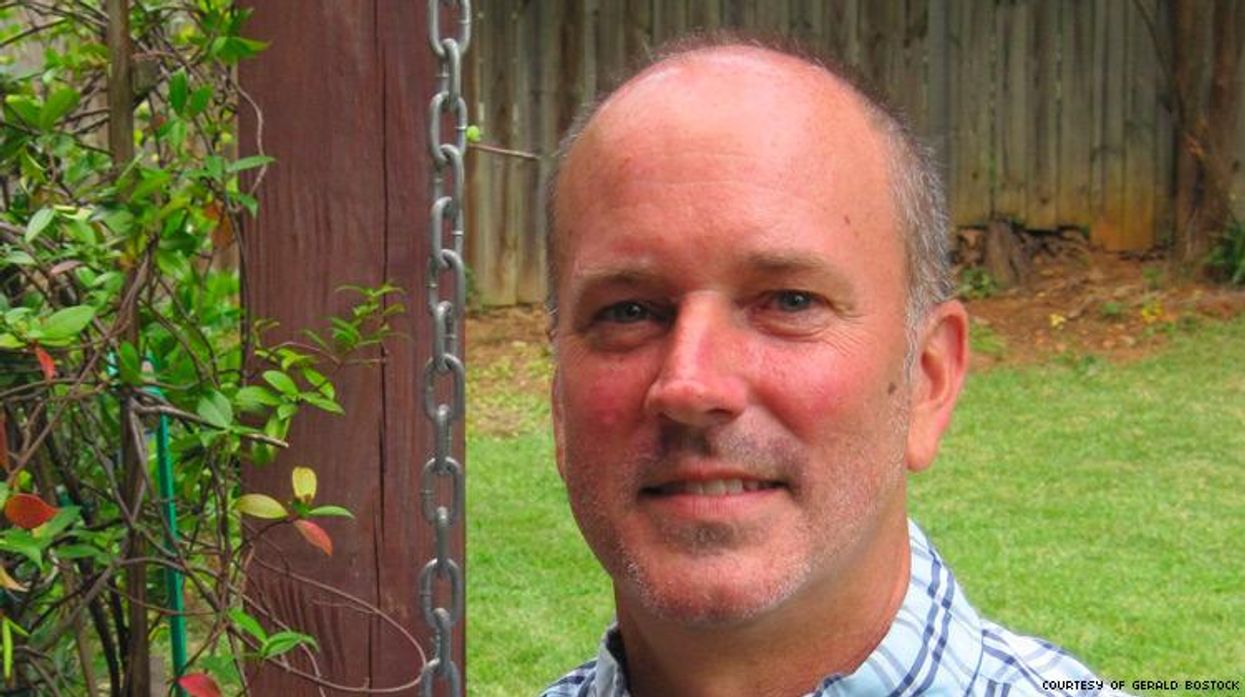

Gerald Bostock's case is one of three the high court will hear Tuesday on whether anti-LGBTQ discrimination is legal.

October 04 2019 1:26 PM EST

trudestress

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Gerald Bostock's case is one of three the high court will hear Tuesday on whether anti-LGBTQ discrimination is legal.

Gerald Bostock didn't expect participation in a gay softball league to cost him his job.

Bostock, a gay man, had been working as child welfare services coordinator assigned to the Juvenile Court of Clayton County, Ga., for a decade when he joined the Atlanta area's Hotlanta Softball League in January 2013. He directed an award-winning program for the county that assigned volunteer advocates to neglected and abused children in the juvenile justice system, and he had received good performance reviews.

And it wasn't like he was closeted at work. He focused on his job when he was working and on his personal life when he wasn't, but "at no point have I ever hid who I was," Bostock tells The Advocate. But his involvement with the softball league, which he found was not only recreational but a good means of recruiting volunteers for his program, drew attention to the fact that he's gay, and there were some disparaging comments from people with influence in the court system. In June of 2013, he was fired, with county officials saying he had mismanaged funds -- totally untrue, he says. The real reason for his dismissal, he says, was his sexual orientation.

Having lost his income and his health insurance while he was recovering from prostate cancer, Bostock quickly fought back. He sued the county in federal court for violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bans sex discrimination. A trial court and a federal appeals court dismissed it, saying that law doesn't cover discrimination based on sexual orientation. Now Bostock has appealed to the Supreme Court, which will hear his case Tuesday, along with two others, likely leading to a definitive decision on the scope of Title VII.

"I'm absolutely very excited to have this opportunity, but it's the same time it's very surreal to me ... it's very much bigger than me," he says.

Bostock's case was consolidated with that of Donald Zarda, a skydiving instructor who said he was fired for being gay (his employer contended it was for inappropriate touching of a woman client). Zarda died in an accident after filing his suit, but his estate has continued to pursue the case. Their cases revolve around whether sexual orientation discrimination qualifies as sex discrimination. The same day the high court hears their cases, it will consider the case of Aimee Stephens, a funeral director fired for being transgender, to determine if discrimination based on gender identity also qualifies as sex discrimination.

The three cases produced what's known as a "circuit split," in legal parlance, among federal appeals courts. In Bostock's case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit said Title VII doesn't extend to sexual orientation discrimination. In Zarda's, the Second Circuit said it does. In Stephens's, the Sixth Circuit said Title VII covers gender identity discrimination. While the Supreme Court generally doesn't say why it decides to take a case, it often accepts those involving an issue that has generated a circuit split.

To Bostock and his lawyer, Brian Sutherland, it's unquestionable that discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity does qualify as sex discrimination -- it's discrimination based on a preconceived notion of how men and women should conduct their lives, who they should partner with, how they present themselves. That conclusion comes from simply reading Title VII, Sutherland says, and it was strengthened by 1989's Supreme Court decision in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, in which the court ruled that sex stereotyping constitutes sex discrimination.

"The Justice Department [which has filed briefs on the issue] and the employers in the case argue that sexual orientation discrimination is not sex discrimination because men and women are treated the same" -- in other words, men and women are discriminated against equally, Sutherland says. That argument is similar to one once made to justify laws against interracial marriage -- supporters of the laws said they weren't discriminatory because all races were subject to them. And it's equally specious, Sutherland says.

"You can't cure discrimination by doubling down on it," he says. "It's wrong and it's immoral."

Sutherland won't be arguing Bostock's case at the Supreme Court -- because of the case consolidation, that duty will go to Pamela Karlan, a professor at Stanford Law School and co-director of the school's Supreme Court Litigation Clinic. "Professor Karlan is excellent," Sutherland says.

He and Bostock will be attending the proceedings, though, and they're optimistic about the outcome (a decision likely won't be announced until next June). Bostock notes that he's had the full support of his partner throughout the process (he chooses to keep his partner's name out of the media), and of other loved ones and his current employer, an Atlanta-area hospital where he works as a mental health counselor.

The fact that his suit was dismissed by both the trial and appeals courts means that he's never had a chance to prove discrimination -- and if the Supreme Court rules that Title VII applies, he will, and he's looking forward to that. His firing, he says, sent a negative message to all LGBTQ people in Clayton County -- especially LGBTQ youth.

No matter what the outcome is, though, he's glad he fought back. "I'm proud of who I am," he says. "I'm also proud of the man I've become and what my work has meant to children. Nobody is going to take that away from me, especially Clayton County."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes